Why Your Bamboo Cutlery Lead Time Depends on Suppliers You've Never Heard Of

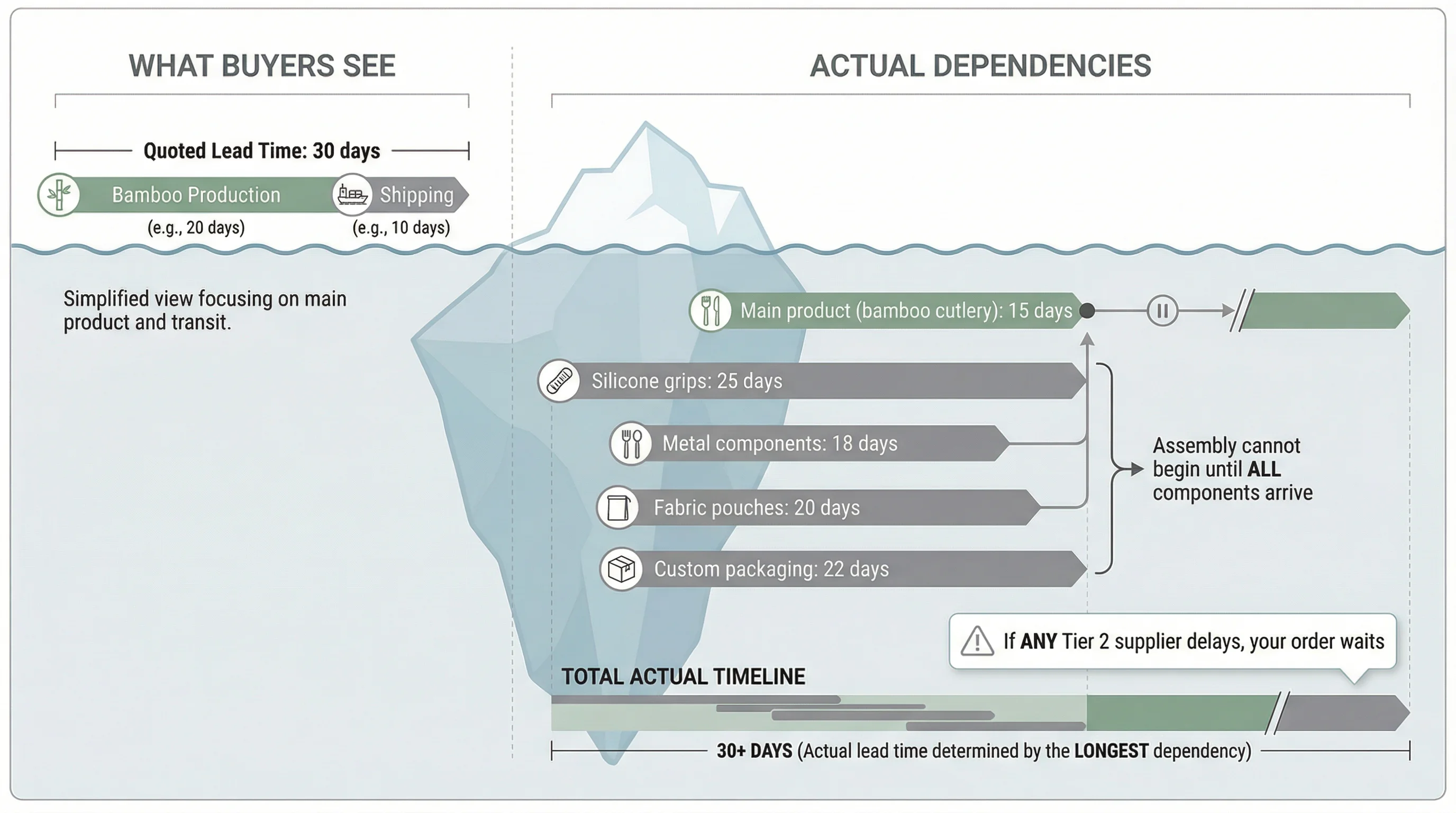

The quoted production time covers only part of the picture. The rest is determined by sub-suppliers you didn't know existed.

When a buyer asks "what's your lead time for this bamboo cutlery order?" the answer they receive typically reflects the time required for the primary manufacturing process—cutting, shaping, finishing, and branding the bamboo pieces themselves. What that number rarely includes is the time required for every other component that must arrive before the order can ship. In practice, this is often where lead time decisions start to be misjudged. The bamboo factory may be ready in three weeks, but if the silicone grips take five weeks and the canvas pouches take four, the order doesn't ship until week five regardless of how efficiently the bamboo production runs.

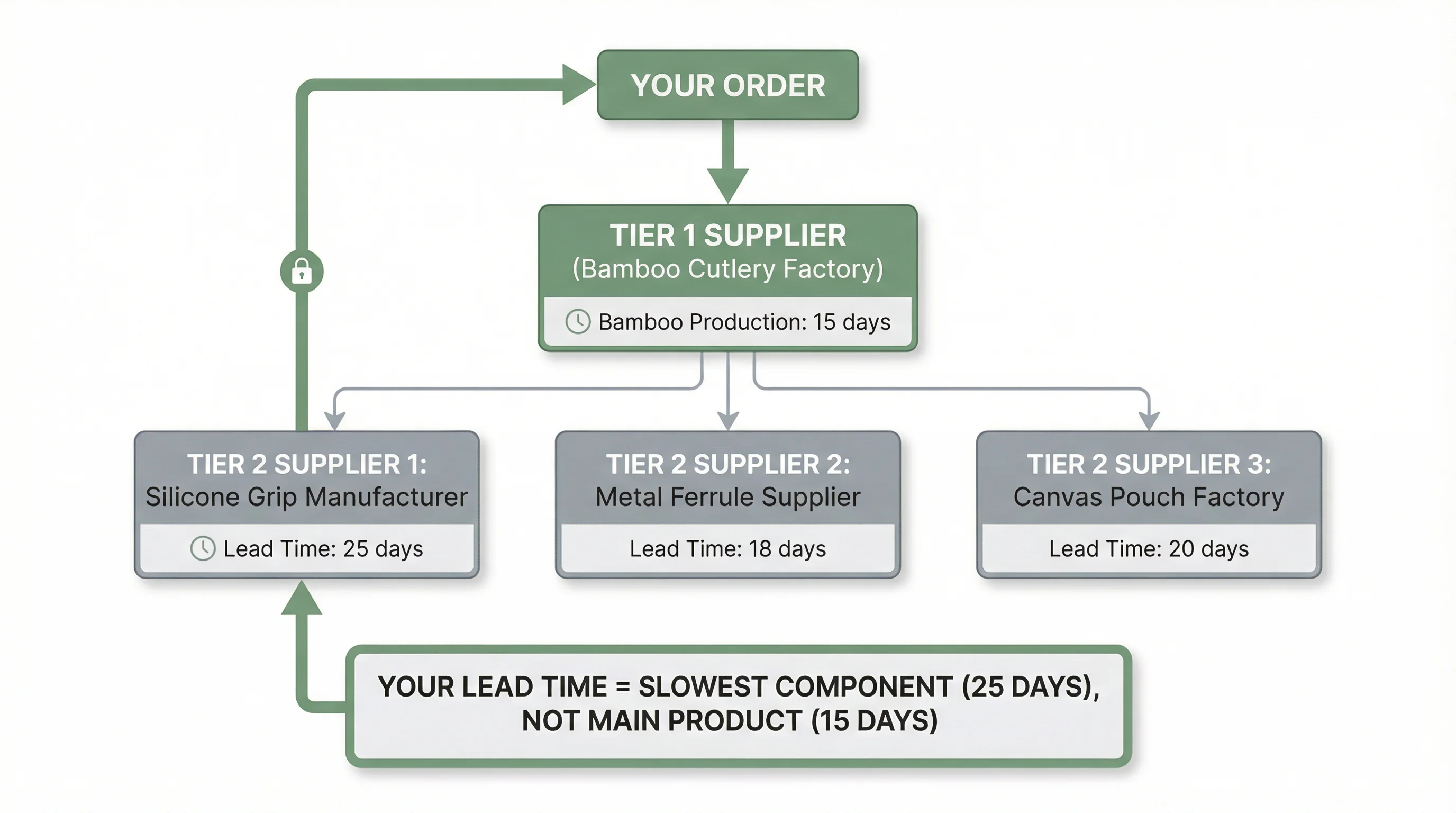

Modern manufacturing, even for seemingly simple products like wooden or bamboo cutlery, operates through layered supply networks. The factory you're working with—your Tier 1 supplier—specialises in bamboo processing. They have the equipment, expertise, and workforce to transform raw bamboo culms into finished utensils. What they typically don't have is the capability to mold silicone, cast metal components, weave fabric, or print custom packaging. These elements come from their own suppliers, the Tier 2 layer of the supply chain. And those Tier 2 suppliers have their own production queues, their own raw material constraints, and their own capacity limitations that your Tier 1 supplier cannot directly control.

The challenge becomes acute when orders involve product configurations beyond basic bamboo utensils. Consider a corporate gift set: bamboo cutlery with silicone grip handles, packed in a canvas roll-up pouch, placed inside a custom-printed kraft box with a branded belly band. The bamboo cutlery itself might require fifteen working days to produce. But the silicone grips need to be molded and cured—that's a separate factory with a twenty-five day lead time. The canvas pouches require cutting, sewing, and quality inspection—another factory, another twenty days. The kraft boxes need printing, die-cutting, and folding—yet another supplier, another eighteen days. The belly bands require their own printing run.

None of these timelines run in isolation. They all need to converge at the Tier 1 factory before final assembly and packing can begin. If the silicone grips arrive on day twenty-five but the canvas pouches don't arrive until day twenty-eight, the entire order waits. The bamboo cutlery, finished and ready since day fifteen, sits in the warehouse. The silicone grips, delivered and inspected, sit alongside them. Everything waits for the slowest component to arrive before the assembly line can start putting sets together.

This dependency creates a fundamental asymmetry in how lead time risk distributes across the supply chain. When buyers evaluate suppliers, they typically assess the Tier 1 factory's capabilities, certifications, and track record. They visit the facility, inspect samples, and verify quality systems. What they rarely see—because it's not visible from the Tier 1 relationship—is the network of sub-suppliers that the factory depends upon. A factory might have excellent bamboo processing capabilities and still deliver late because their silicone supplier had a machine breakdown, or their packaging supplier prioritised a larger customer's order, or their fabric supplier faced a raw material shortage.

The information gap compounds the problem. When you ask your supplier for a lead time estimate, they're often providing their own production timeline plus a buffer for sub-components. But that buffer is based on historical averages and normal conditions. It doesn't account for the specific situation at each Tier 2 supplier at the moment your order enters the queue. The silicone factory might be running smoothly when your order is quoted, then experience equipment issues two weeks later when your components are actually being produced. Your Tier 1 supplier may not learn about this delay until the expected delivery date passes without the components arriving.

Understanding how production timelines work requires recognising that the quoted lead time is often the Tier 1 timeline, not the total timeline. For simple orders—standard bamboo cutlery without accessories, packed in generic packaging—the distinction may not matter much. The bamboo production is the critical path, and sub-components are either standard stock items or have shorter lead times than the main product. But as orders become more complex, as customisation increases, as product configurations expand to include multiple materials and accessories, the Tier 2 dependencies increasingly determine the actual delivery date.

The practical question becomes how to identify and manage these hidden dependencies before they cause delays. One approach is to ask explicitly about sub-components during the quotation process. Rather than simply asking "what's your lead time?" the question becomes "what components does this order require, and what's the lead time for each?" This forces visibility into the Tier 2 layer and reveals which components sit on the critical path. If the silicone grips have the longest lead time, that's the number that matters for planning purposes, not the bamboo production time.

Another approach involves timing the order placement to allow parallel production across the supply chain. If you know the silicone grips take twenty-five days and the bamboo takes fifteen days, placing the silicone order ten days before the bamboo order means both components finish around the same time. This requires coordination with the Tier 1 supplier and often requires committing to sub-component orders before the final product design is fully locked. But it can compress the total timeline significantly compared to sequential ordering where each component waits for the previous one to be confirmed.

Some buyers choose to source sub-components directly, removing the Tier 2 dependency from their Tier 1 supplier's scope. If you purchase the silicone grips yourself and ship them to the bamboo factory, you control that timeline directly. You can monitor the silicone supplier's progress, expedite if necessary, and ensure components arrive when needed. The trade-off is complexity—you're now managing multiple supplier relationships instead of one, and you're responsible for coordinating the logistics of getting components to the right place at the right time.

The most consequential insight is that lead time questions need to be asked differently for complex orders. "What's your lead time?" assumes a single answer that captures the full picture. For orders involving multiple materials, accessories, and custom packaging, the more useful questions are: "What are all the components required for this order? Which components do you manufacture in-house versus source externally? What's the lead time for each external component? Which component has the longest lead time, and does that determine when my order can ship?" These questions surface the Tier 2 dependencies that often remain invisible until they cause delays.

The underlying reality is that your bamboo cutlery order is only as fast as its slowest component. A factory can have world-class bamboo processing capabilities, impeccable quality systems, and a dedicated production team—and still deliver your order late because a sub-supplier they've used reliably for years had an unexpected capacity issue. Recognising this dependency structure doesn't eliminate the risk, but it does enable more realistic planning and more informed conversations about what "lead time" actually means for your specific order configuration.