Why Sample Approval Doesn't Mean What You Think

The gap between what buyers expect from sample approval and what factories interpret it to mean causes more disputes than any other stage in sustainable tableware customisation.

When a procurement team signs off on a pre-production sample of branded bamboo cutlery, there's an implicit assumption that the 3,000 units arriving eight weeks later will be identical to the item sitting on their desk. This assumption is where most customisation disputes originate, and it stems from a fundamental misunderstanding about what sample approval actually represents in manufacturing terms.

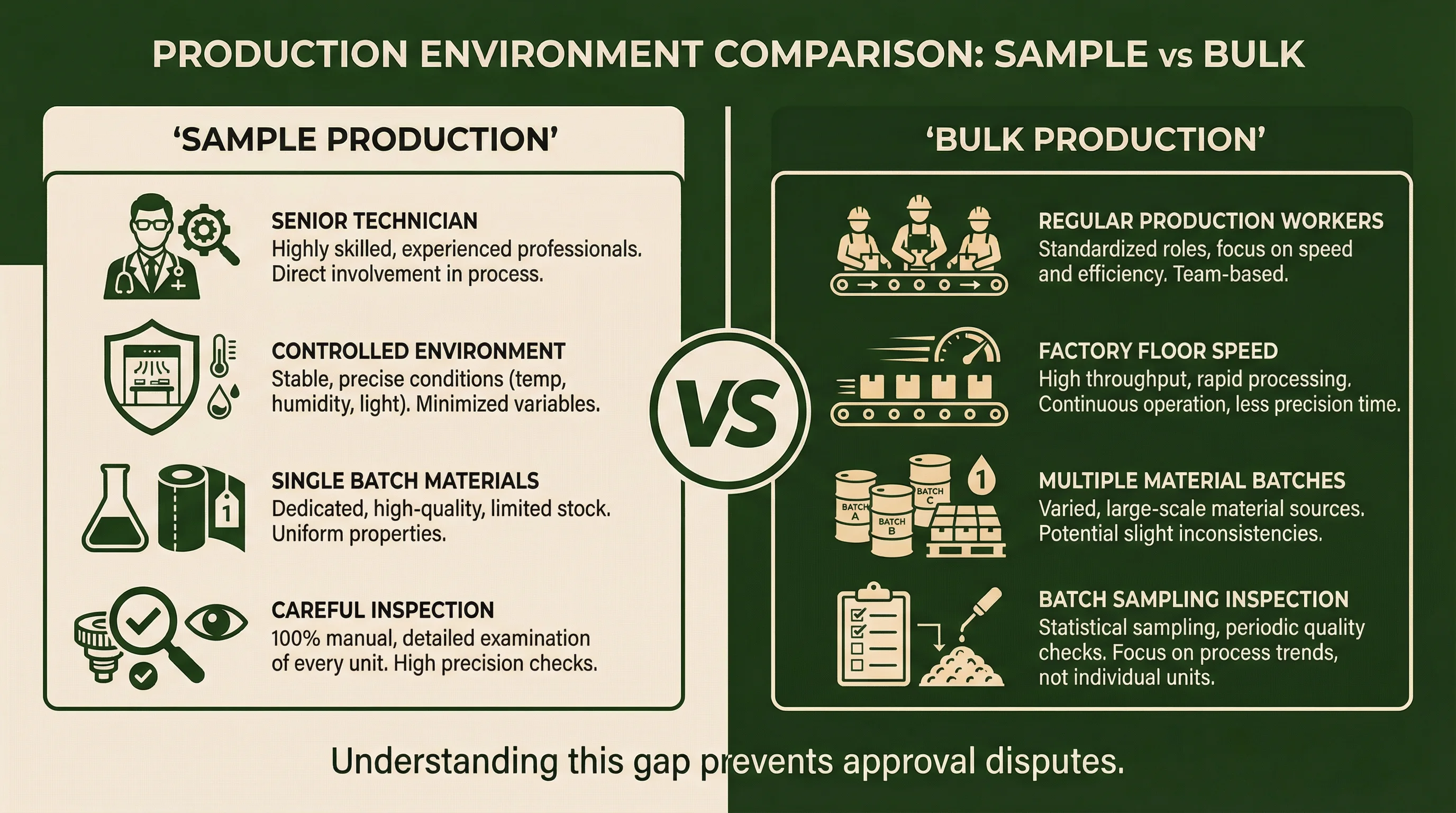

The sample you approve is typically produced by a senior technician in a controlled environment, using materials from a single batch, with careful attention to every detail. This is not how bulk production operates. Understanding this distinction doesn't diminish the value of sampling—it simply recalibrates expectations so that the final delivery doesn't become a source of conflict.

In practice, this is often where customisation decisions start to be misjudged. A buyer approves a sample expecting pixel-perfect replication, while the factory interprets approval as acceptance of a target standard with industry-normal variation. Neither party is wrong in their interpretation—they're simply operating from different frameworks that were never explicitly aligned.

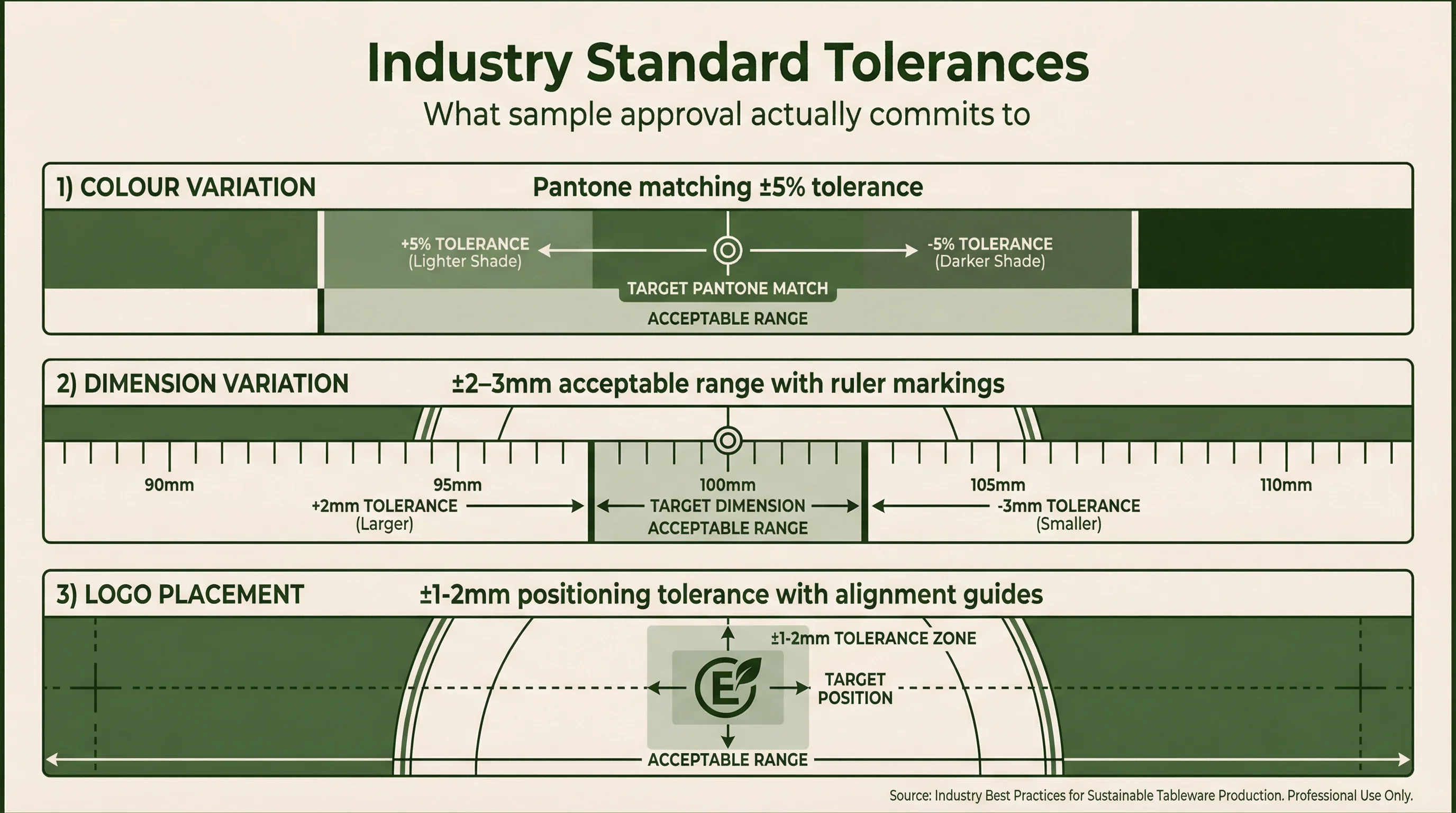

Consider the colour matching process for a corporate logo on wheat straw plates. The sample might achieve a near-perfect Pantone match because the technician selected the best substrate pieces from the batch and adjusted ink density during printing. In bulk production, natural material variation means some plates will have slightly different base colours, affecting how the printed logo appears. This is not a quality failure—it's the inherent characteristic of working with organic materials.

The tolerance ranges that govern manufacturing are rarely discussed during the sampling phase, yet they define what constitutes acceptable variation in the final delivery. For sustainable tableware, these tolerances exist because natural materials behave differently from synthetic alternatives. Bamboo grain patterns vary. Wheat straw density fluctuates between harvests. Recycled stainless steel may have subtle surface texture differences. These variations are features of sustainable production, not defects.

The practical consequence of this misalignment becomes apparent when bulk goods arrive. A procurement manager compares the shipment to the approved sample and notices the logo colour appears slightly darker on some pieces, or the engraving depth varies marginally across the batch. Without understanding tolerance frameworks, this triggers a rejection or dispute. The factory, operating within standard parameters, is genuinely confused by the complaint.

What makes this particularly problematic for New Zealand buyers is the distance involved. Resolving disputes with overseas manufacturers takes time—time that often doesn't exist when products are needed for a specific event or campaign launch. The shipment sits in a warehouse while emails go back and forth, and the original deadline passes. This scenario is preventable, but only if expectations are calibrated before sample approval, not after bulk arrival.

The solution isn't to demand tighter tolerances—that approach simply increases costs and extends timelines without eliminating variation entirely. Instead, the approval process itself needs to be more explicit. When reviewing a sample of branded reusable cutlery, the conversation should include what variation is acceptable, not just whether the sample itself meets requirements. This shifts the approval from a binary yes/no decision to a documented agreement about acceptable ranges.

Some organisations address this by requesting multiple samples rather than a single piece. Seeing three or four samples from the same production run reveals the natural variation range before bulk commitment. If the variation between samples is already uncomfortable, that's valuable information—it indicates what to expect at scale, and whether the product specification needs adjustment before proceeding.

The broader point extends beyond any single order. Organisations that understand the relationship between sample approval and production reality tend to have smoother supplier relationships and fewer last-minute crises. This understanding is part of what separates experienced procurement teams from those still learning the nuances of sustainable tableware customisation. The sample is a reference point, not a promise of identical replication—and recognising this distinction early prevents significant frustration later.