When Accepting a Higher MOQ Actually Costs Less

A procurement strategist's perspective on the counter-intuitive economics of order quantities

There is a moment in nearly every corporate gift procurement project when the conversation turns to minimum order quantities. The supplier states their threshold—perhaps 500 units, perhaps 2,000—and the buyer's instinct is to push back. Negotiating a lower MOQ feels like a win. It preserves cash flow, reduces storage burden, and demonstrates procurement competence to internal stakeholders. Yet after fifteen years of advising organisations on B2B gifting programmes, I have watched this instinct lead to outcomes that cost far more than the original MOQ would have.

The issue is not that negotiating lower quantities is inherently wrong. The issue is that most procurement teams evaluate MOQ decisions using incomplete criteria. They compare the quoted unit price at different quantities, factor in warehouse space, and stop there. What they fail to account for are the second-order effects that only become visible months later: the quality variance that emerges when your order sits at the bottom of the production queue, the relationship capital spent on aggressive negotiation, and the administrative overhead of managing multiple smaller orders across a fiscal year.

Consider a scenario that plays out regularly in corporate gifting. A procurement manager needs 800 custom-branded bamboo cutlery sets for an annual sustainability event. The supplier quotes $4.20 per unit at their standard MOQ of 1,000 units, or $5.80 per unit for a special accommodation of 800 units. The manager celebrates securing the lower quantity—after all, they have avoided purchasing 200 "unnecessary" units. The total spend is $4,640 instead of $4,200, but the manager rationalises this as avoiding storage costs and potential waste.

What this calculation misses is the production reality. When a factory accepts an order below their standard MOQ, that order typically receives lower scheduling priority. The production line is optimised for standard batch sizes, and accommodating a smaller run often means squeezing it between larger orders or running it during off-peak hours with less experienced operators. The result is frequently a higher defect rate—not dramatic enough to trigger a formal quality complaint, but sufficient to produce items that feel slightly inconsistent. Logos that are marginally off-centre. Packaging that arrives with minor scuffs. These imperfections may seem trivial until the gifts are distributed to clients or partners who notice the difference.

The relationship dimension is equally significant. Suppliers remember which buyers consistently push for exceptions. This does not mean they will refuse future orders, but it does influence how they allocate capacity during peak seasons, how quickly they respond to urgent requests, and how much flexibility they offer when genuine problems arise. A procurement team that has spent its relationship capital negotiating every MOQ down will find that capital unavailable when they truly need it—when a shipment is delayed, when a design error requires rapid correction, or when market conditions create genuine supply constraints.

There is also the question of what happens to those "unnecessary" units that the lower MOQ was meant to avoid. In many organisations, the 200 additional cutlery sets would not sit in storage indefinitely. They would be absorbed by the HR department for onboarding kits, held as backup for damaged items, or allocated to a smaller regional event that would otherwise require a separate order. The perceived waste often represents genuine future demand that simply has not been formally requisitioned yet. By ordering only what is immediately needed, the procurement team creates a situation where the next request triggers an entirely new procurement cycle—with its own setup costs, shipping fees, and administrative burden.

The Mathematics of Split Orders

Suppose the organisation does need those additional 200 units six months later. At that point, they face a choice: place another small order at the premium rate, or wait until demand accumulates to meet the standard MOQ.

The "savings" from negotiating a lower quantity transforms into a 38% cost increase when future demand materialises.

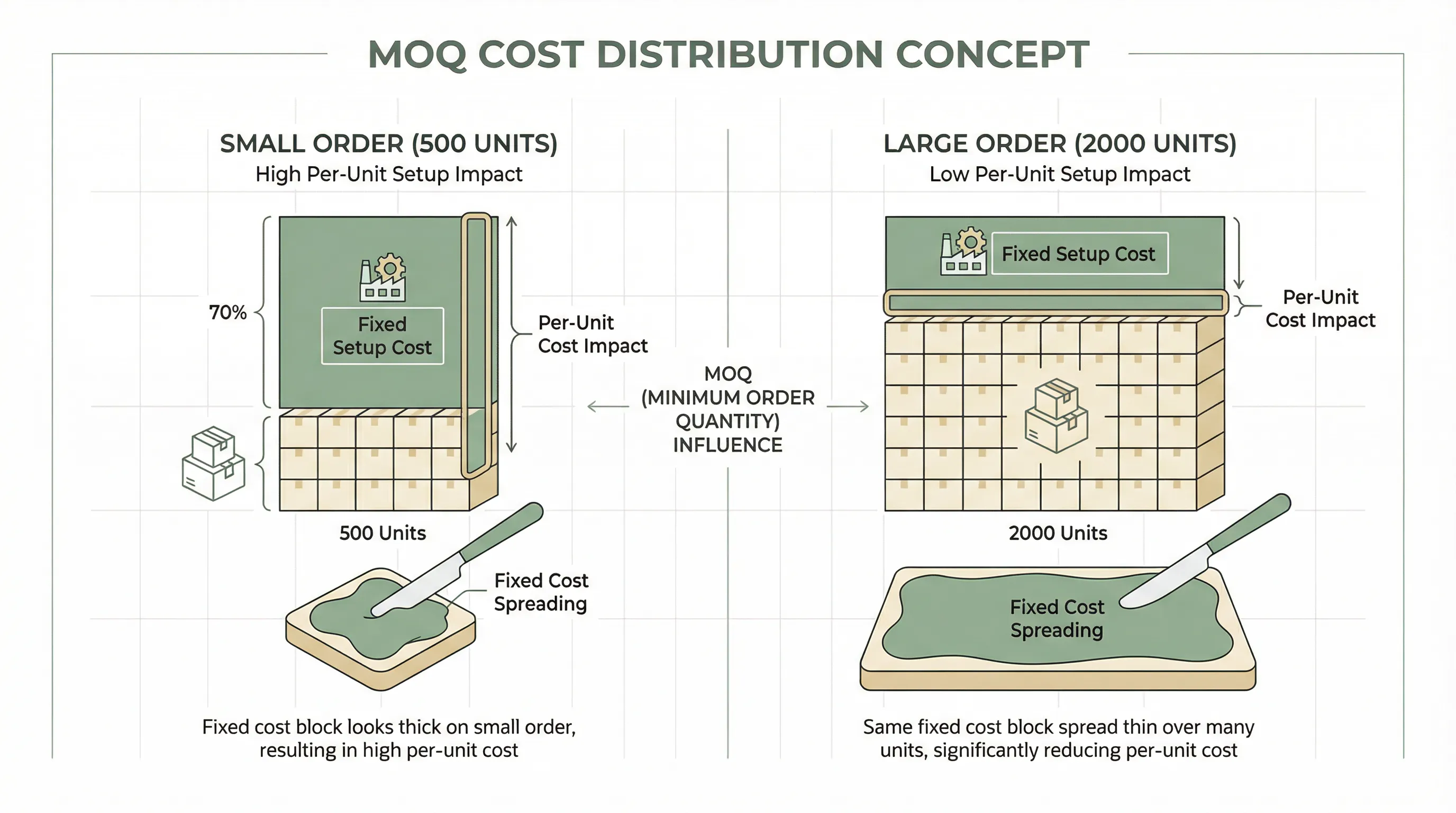

This pattern becomes even more pronounced with custom-branded items, where setup costs represent a larger proportion of total expense. Laser engraving equipment must be calibrated for each design. Printing plates must be prepared. Quality control samples must be produced and approved. These fixed costs exist regardless of whether the final order is 500 units or 5,000 units. When spread across a larger order, they become negligible on a per-unit basis. When concentrated in a small batch, they can double or triple the effective unit price.

The practical question for procurement teams is not whether to accept every MOQ without question—that would be equally misguided. The question is how to evaluate when acceptance serves the organisation's interests better than negotiation. Several factors warrant consideration.

First, examine the supplier's production structure. Some MOQs reflect genuine operational constraints: the minimum quantity of raw materials that can be efficiently processed, the setup time required for customisation equipment, or the batch sizes that quality control processes are designed to handle. Other MOQs are primarily commercial—thresholds set to ensure profitability rather than operational necessity. Understanding which category applies helps determine whether negotiation is likely to succeed without creating downstream problems.

Second, project forward demand with realistic assumptions. Corporate gifting is rarely a one-time activity. Events recur annually. Employee milestones continue. Client relationships require ongoing cultivation. If your organisation will need similar items within the next twelve months, the "excess" inventory from a higher MOQ may simply be advance procurement at a better price point.

Third, calculate the true cost of multiple smaller orders versus a single larger one. Include not just unit prices but shipping costs (which rarely scale linearly with quantity), administrative time for purchase orders and approvals, quality inspection effort, and the opportunity cost of procurement staff managing multiple transactions instead of focusing on strategic initiatives.

Fourth, consider the supplier relationship in its full context. If this is a vendor you expect to work with repeatedly, the goodwill preserved by accepting reasonable MOQs may prove more valuable than the immediate savings from negotiating exceptions. Conversely, if this is a one-time transaction with a supplier you are unlikely to use again, the relationship consideration carries less weight.

The most effective procurement professionals I have worked with approach MOQ discussions not as adversarial negotiations but as collaborative problem-solving. They ask suppliers to explain the factors driving their MOQ requirements. They share their own constraints openly. They explore creative solutions—perhaps accepting the standard MOQ but arranging for staggered delivery, or combining orders across departments to reach volume thresholds naturally. This approach often yields better outcomes than aggressive negotiation, because it addresses the underlying interests of both parties rather than treating the MOQ as a number to be beaten down.

None of this suggests that procurement teams should accept every MOQ without scrutiny. Inflated thresholds do exist, and some suppliers use MOQ requirements as a screening mechanism rather than an operational necessity. The point is that the instinct to negotiate lower quantities should be examined rather than automatically followed. In many cases, the procurement "win" of securing a reduced MOQ proves to be a loss when all costs are properly accounted.

For organisations navigating the complexities of sustainable corporate gifting, where material sourcing, customisation, and compliance requirements add layers of complexity, understanding these dynamics becomes particularly important. The decision about how many units to order involves more than simple arithmetic. It requires thinking through production realities, relationship implications, and the full lifecycle of procurement needs. When that analysis is done thoroughly, accepting a higher MOQ often emerges as the more strategic choice.