Why Ordering More Bamboo Cutlery to Meet MOQ Can Cost You Through Inventory Degradation

Understanding how natural material shelf life interacts with minimum order quantities, and why the economics of bulk ordering change when products are not shelf-stable

The calculation seems straightforward. A supplier quotes 3,000 bamboo forks at a unit price that drops significantly compared to the 1,500-unit tier. The procurement team runs the numbers: even accounting for the excess inventory, the lower per-unit cost appears to generate savings. The order is placed. Eighteen months later, the facilities manager discovers that the remaining 800 forks in storage have developed visible discolouration, and a portion show early signs of surface mould. The "savings" from the bulk order have evaporated, replaced by disposal costs and an emergency reorder at standard pricing.

This pattern repeats across organisations that apply conventional inventory economics to natural materials without accounting for a fundamental difference: bamboo and wooden cutlery are not shelf-stable in the way that plastic or stainless steel alternatives are. The materials continue to interact with their environment after manufacturing, and that interaction has consequences that compound over time. When minimum order quantity decisions force buyers to hold inventory longer than the material's practical shelf life, the economics of the original purchase become meaningless.

The MOQ decision is not just about how much to buy—it is about how long you will need to store what you buy, and whether the material can tolerate that storage duration.

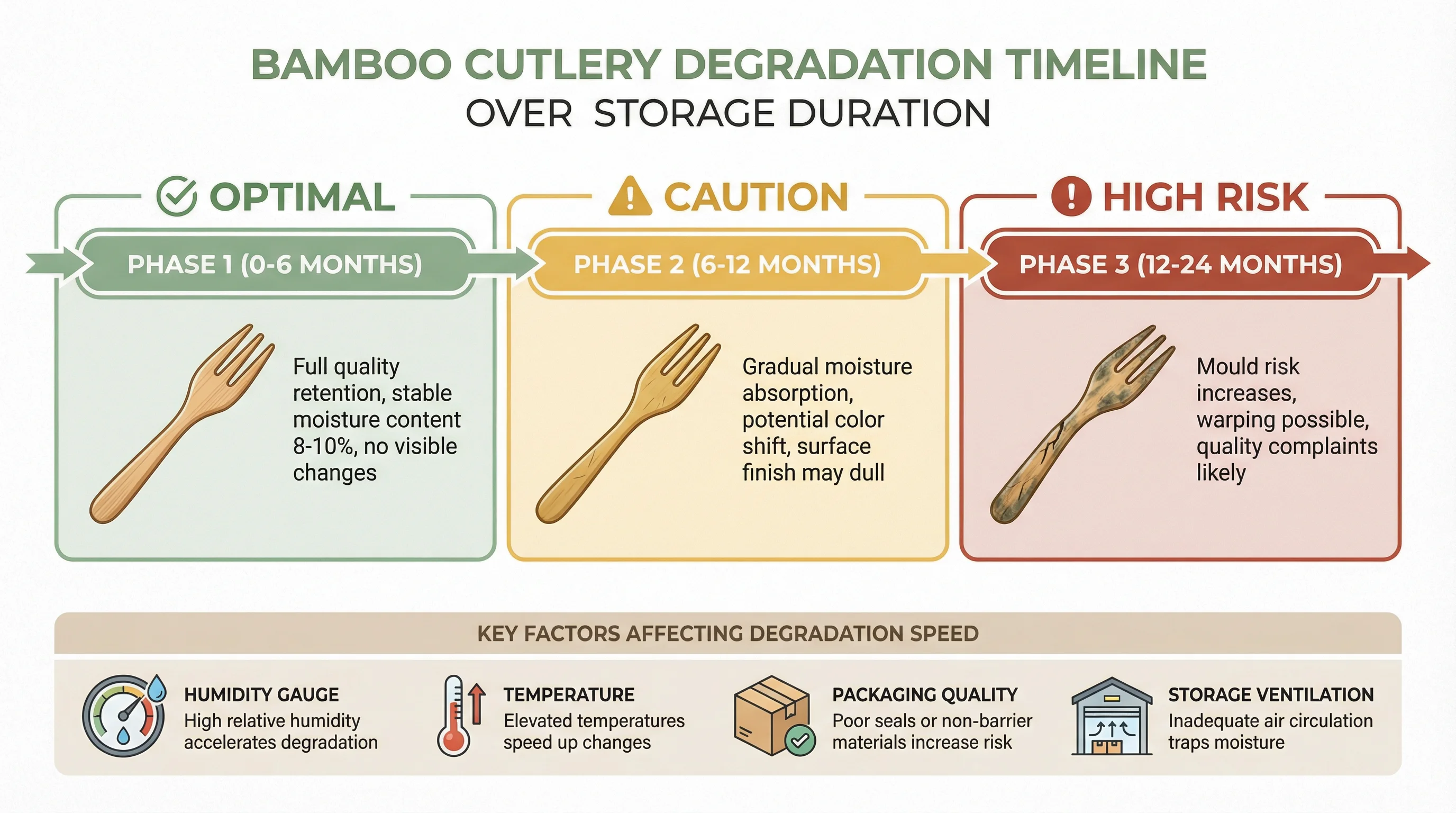

Bamboo, as a lignocellulosic material, maintains an equilibrium moisture content with its surrounding environment. In a warehouse with 65% relative humidity, bamboo cutlery will gradually absorb moisture until it reaches equilibrium with that environment. In a drier storage area, it will release moisture. These moisture fluctuations are not merely cosmetic concerns. They affect dimensional stability, surface finish integrity, and most critically, they create conditions that can support biological growth. A bamboo fork that left the factory at 8% moisture content may reach 14% moisture content after six months in a poorly controlled storage environment—and at that moisture level, the risk of mould colonisation increases substantially.

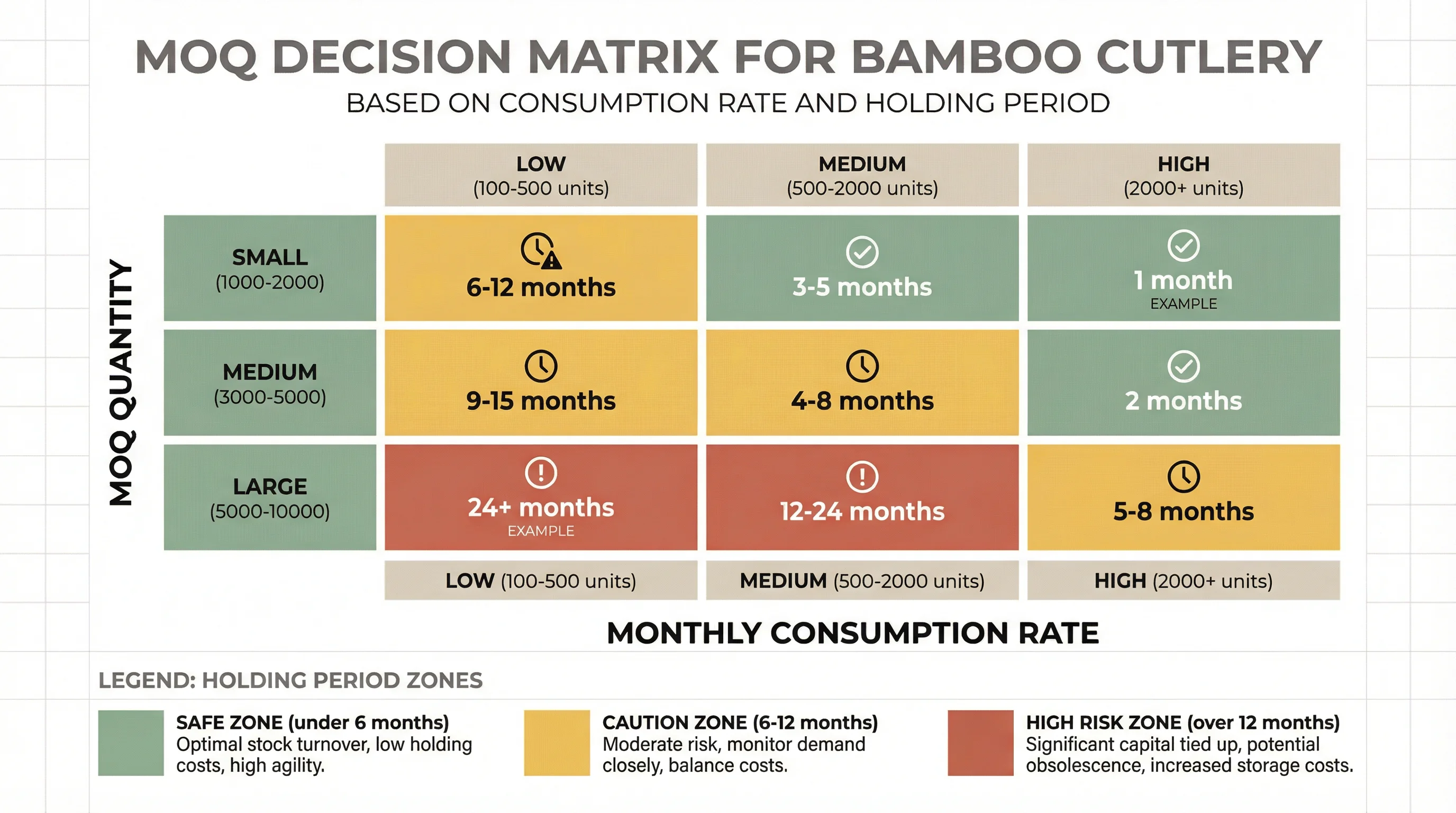

The practical implication is that MOQ decisions for bamboo and wooden cutlery must incorporate a variable that rarely appears in standard procurement calculations: the expected consumption rate relative to the material's storage tolerance. A hospitality group operating fifteen cafes might consume 3,000 bamboo forks monthly. For that buyer, a 5,000-unit MOQ represents less than two months of inventory—well within the safe storage window for properly handled bamboo products. The same 5,000-unit MOQ for a corporate office that uses 200 forks monthly represents over two years of inventory. At that holding duration, even excellent storage conditions may not prevent quality degradation.

The degradation pathway varies by product type and finish. Unfinished bamboo cutlery is more susceptible to moisture absorption and surface changes than pieces treated with food-safe oils or waxes. However, even finished products have finite protection—the surface treatment itself can degrade over extended storage, particularly if the products are exposed to temperature cycling or UV light. Wooden cutlery made from beech or birch follows similar patterns, though the specific moisture thresholds and degradation rates differ based on wood species and density.

What makes this particularly problematic for procurement planning is that the degradation is often invisible until it becomes severe. A bamboo spoon that has absorbed excess moisture may look identical to a properly stored piece until it develops visible mould spots or warping. By the time the quality issue becomes apparent, the affected inventory may have been in storage for months, and the window for supplier claims or returns has typically closed. The buyer discovers the problem when attempting to use the inventory, not when the degradation actually occurred.

Storage conditions matter enormously, but they are rarely within the procurement team's direct control. The warehouse environment, the proximity to loading docks that experience temperature and humidity swings, the quality of packaging that protects against moisture ingress—these factors determine whether a twelve-month inventory holding period is manageable or disastrous. Organisations that lack climate-controlled storage or that store products in areas with significant environmental variation face higher degradation risk, which should factor into their MOQ decisions but rarely does.

The New Zealand context adds specific considerations. The country's maritime climate produces humidity levels that vary significantly by region and season. Auckland's average relative humidity exceeds 80% for much of the year. Canterbury experiences drier conditions but with greater seasonal variation. A bamboo cutlery inventory that performs well in a Wellington warehouse during winter may face different challenges during a humid summer. Organisations operating across multiple regions may find that the same product ages differently depending on where it is stored.

In practice, this is where MOQ-related decisions start to be misjudged. The procurement team evaluates supplier quotes based on unit pricing at different quantity tiers, calculates the apparent savings from ordering at higher volumes, and selects the option that minimises per-unit cost. The calculation treats the purchased inventory as a static asset that retains its value indefinitely. For synthetic materials, this assumption is largely valid—a plastic fork purchased today will be functionally identical in three years. For bamboo and wooden cutlery, the assumption fails. The inventory is a depreciating asset from the moment it enters storage, and the depreciation rate depends on factors that the procurement team may not have visibility into.

The more sophisticated approach requires incorporating expected holding duration into the MOQ evaluation. If a 5,000-unit order at a lower per-unit price results in an eighteen-month inventory holding period, and the buyer's storage conditions create meaningful degradation risk beyond twelve months, the apparent savings must be weighed against the probability of partial inventory loss. A 3,000-unit order at a higher per-unit price that results in a nine-month holding period may actually deliver better value when degradation risk is factored in.

Some organisations attempt to mitigate this risk through inventory rotation protocols—first-in-first-out systems that ensure older stock is used before newer arrivals. These protocols help but do not eliminate the underlying issue. If the total inventory holding period exceeds the material's practical shelf life, rotation simply determines which portion of the inventory degrades, not whether degradation occurs. The fundamental mismatch between order quantity and consumption rate remains.

For buyers navigating minimum order requirements for sustainable cutlery, the degradation dimension adds complexity that standard procurement frameworks do not address. The lowest per-unit cost is not necessarily the lowest total cost of ownership when the product has a finite shelf life. The "savings" from bulk ordering can be entirely consumed by quality losses if the resulting inventory holding period exceeds what the material can tolerate. And the risk is asymmetric—the buyer bears the full cost of degraded inventory, while the supplier's obligation typically ends at delivery of conforming product.

The practical response is not to avoid bulk ordering entirely, but to calibrate order quantities against realistic consumption projections and honest assessments of storage capabilities. An organisation with climate-controlled storage, robust inventory management systems, and high consumption rates can safely accept larger MOQs. An organisation with variable storage conditions, limited inventory visibility, and modest consumption rates should prioritise order frequency over order size, even if that means accepting higher per-unit pricing. The goal is not to minimise the price paid per unit, but to minimise the cost per unit actually consumed—and those two figures diverge when inventory degradation enters the equation.

Suppliers who understand this dynamic can sometimes offer solutions that buyers do not think to request. Scheduled shipments against a single order, allowing the buyer to commit to total volume while receiving inventory in tranches that match consumption. Packaging configurations that extend shelf life by providing better moisture barriers. Storage guidance that helps buyers maintain product quality through the holding period. These accommodations add complexity to the supplier relationship but can preserve the economic value of bulk ordering while managing degradation risk.

The underlying principle is that natural materials require procurement approaches that account for their biological nature. The same thinking that makes bamboo and wooden cutlery attractive from a sustainability perspective—these are organic materials that will eventually return to the earth—also means they are not indefinitely stable in storage. MOQ decisions that ignore this reality optimise for the wrong variable, generating apparent savings that disappear when the inventory is actually needed.